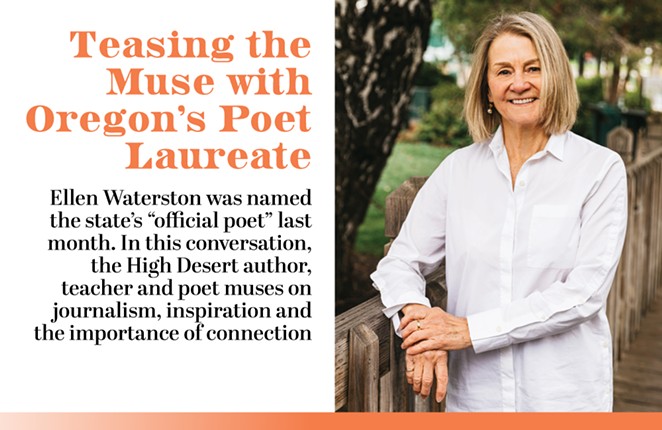

In the United States, 45 of our 50 states have an official poet laureate designation — empowering one local wordsmith in each state to promote the appreciation of reading, writing and creativity in general. In Oregon, that person is now Central Oregon's own Ellen Waterston, who's been promoting the beauties of the written word through workshops, classes, events and more for decades. We at the Source Weekly are also proud to publish her column on ageism and ageing, "The Third Act," the fourth week of each month.

We published a news story on her appointment to the position of Oregon Poet Laureate by Gov. Tina Kotek last month, but in this feature, we take a deeper dive with Waterston about the purpose of poetry, how she got started, what Artificial Intelligence brings to the creative process and so much more. Answers have been lightly edited for clarity.

Source Weekly: When we did our initial interview with you about the Poet Laureate designation, you talked about being an elder, and hoping to help people recognize the experience and value that elders bring. That said, you've also said that working with youth is a big goal.

Ellen Waterston: Part of the mission, generally, for the Poet Laureate, is to visit schools, work with classrooms, work with, from what I gather, high school students, but middle students as well.

So when I go to communities, my hope is to work with community centers and or other gathering places for those of us of a certain age, and also with the youth and have that be side by side, you know? So, I am not exclusively focusing on elders. What I picture, for example, is maybe a reading at the end of visiting a community and working with a bunch of people, and then maybe an elder and a student and I do some something together.

SW: I'm curious about a time when you were a budding writer, and you weren't sure what it was all about, or what you were doing and how you moved through it.

EW: Well, I guess the story is that I had what so many people talk about — a teacher in high school who woke me up to the power of the written word and also poetry. So I was at a school —not unusual on the East Coast — off to a boarding school for the high school years, in New Hampshire. Robert Frost came and visited the campus. And so between that and this English teacher, it clicked. And I'm from a household that words mattered, OK, so it just started to feel like home. It felt like home. It did. I think it probably must be a feeling other artists experience when they find the discipline that they want to put more time into.

SW: OK, so you're in high school, you feel strongly about writing and poetry, and then what do you do next?

EW: At college, it was more of a journalistic bent. I wound up studying poetry as an undergraduate, but I also was a stringer for "Time" magazine. They appointed what they call stringers on various campuses. And if there was a national story, they would contact the stringer to see what the perspective was from that campus, if campuses were somehow implicated in the topic of the story. So that was wonderful. It started to be all that deadline stuff, and a sense of what that is. I then subsequently got a job on a magazine, still as an undergraduate, during the summer, at "Boston" magazine. That was a little more featurey, but same kind of thing, where getting something produced on deadline was healthy. Not that in school there weren't "deadlines" where we had to turn it in. But it just felt like a bigger world, a bigger conversation, bigger sort of geography that your words are moving out across.

There's beauty in the expression of pain and loss, and there's beauty in the expression of — I want to say hope, but I don't know if I really want to say hope — just the commitment to carrying on, just the belief that life and humans are capable of better —Ellen Waterston

SW: I'm always curious about — obviously, this is my own path too — choosing journalism as a way to be able to write and get paid and have something out in the world. Do you still see that as a viable path for young writers?

EW: Often in my workshops, people will say, I'm not really a writer, I've just been doing tech writing, or I'm not really a writer, I've just been writing promo pieces. And frankly, all of it is training, as you well know. All of it is training about stringing words together in a way that moves a reader in a direction or another. And in creative writing, it's a big, big landscape. There's a lot of colors in that box of paints that you can choose to work with. So it gets more exciting. But I think that that kind of training of being on deadline, having to produce something in writing, and of course — I don't even know what to say about AI and its assistance in this regard now, but of course, that didn't exist before. You were on your own.

SW: I mean, one personal aside. I'm recording this into an AI transcription service that generates the transcription instantly, and in the end, gives me a summary of what we talked about. It's incredible.

EW: I hope you put that in the article!

SW: It doesn't always pick up on nuance around every topic, but it's pretty dang slick. But that gets me thinking. We had an interview. I interviewed you one on one. I asked you to do this. I could also easily just generate a quick little story from the summary. Is that too far? Is that my creative process? A lot of questions around that.

EW: Is there's something to me that the experience, the thrill, especially in creative writing, perhaps in professional writing, which an interview kind of is, but in creative writing, obviously there are ways to use this AI similarly to what you're doing right now. But I really feel that experiencing the collision of certain words side by side, and what that opens up and where that takes you. It's just limited. It's, it's like some sort of bubble wrap or something that's been put around the creative process.

I feel when I work with people, one on one in workshops, and I see these little mini explosions of creativity — it can't happen. I don't think it can happen with AI, because it's like, there's somebody else in the bed.

SW: It's certainly going to be become a thing throughout your tenure. I'm sure even more than it is right this second. It's going to come up a lot.

EW: Yes, it will.

SW: What is something that you're working on right now in the poetry space that you're excited about?

EW: Before the Poet Laureate appointment, I had started a new collection of poetry. A lot of it has been prompted by the opportunity to write poems for a variety of functions that are taking place out in nature in Oregon — for land use groups, for In a Landscape — that being Hunter Noack, with his grand piano, showing up in locations all over Oregon and the West, and I being invited to present a poem in conjunction with a concert, that kind of thing. And they start to be a sort of geography lessons, in a way. And so, I'm expanding on that. And I'm on track to produce a new collection pretty soon.

SW: As part of this story, we're publishing a couple of your poems. Share a little about the theme of those.

EW: What I want to do is reinforce the high desert-ness of this appointment; of this writer; of this language. I want to share my gratitude to Tina Kotek, to the Oregon Cultural Trust and to Oregon Humanities for keeping this going, for keeping the poet laureateship going in the state, and by virtue of the fact that I'm a poet east of the Cascades.

SW: What in your mind do programs like the Poet Laureate bring to a community?

EW: I think the fact that this state designates a poet to be the ambassador for poetry in whatever way they design, whatever way shape or form it takes, given each individual poet that receives this appointment, in and of itself is just magic, right? And there are many, many states that also have Poets Laureate, and there are some that do not. What I see is that it underscores, again, back to what we were originally saying. It underscores the importance of communication, all the ways we can communicate, and particularly with poetry, with the compression of emotion, of description, of the senses, basically a compression of story. And you know, it doesn't have to be two stanzas, it doesn't have to be a haiku. It can be a ballad, it can be a narrative poem. So poetry is very, very flexible. It's enormously elastic. And however, to designate someone to go about the state and encourage people to think creatively with writing. It's so exciting to me, because I've spent a long time on the soapbox trying to get people to love words, and I'm just honored to have the opportunity to do this.

SW: Picking up on that — the part about all the ways we can communicate. Is it a poet laureate's job to address things like climate change and gun violence, racism, existential threats?

EW: I don't know if you saw the article today in "The New York Times" about this wonderful teacher who continues to teach in Ukraine, and asking her students to express what they're feeling about being up close and personal with war, losing friends, having to move, evacuate, there's towns being destroyed. There's beauty in the expression of pain and loss, and there's beauty in the expression of — I want to say hope, but I don't know if I really want to say hope — just the commitment to carrying on, just the belief that life and humans are capable of better. And so, to your question about, should we talk about climate change and politics and racism? Yeah, I mean, I think part of the conversation is, how do we embrace each other through words? And what's in the way of that, what's in the way of that embrace. And there are many, many efforts, the High Desert Partnership in Burns, right? That brings all kinds of people together to talk about — whether they're involved with government, whether they're involved with environmental organizations, whether they are ranchers, whether they're citizens, whatever, to try to find common ground, right, this notion of common ground.

So I think poetry is one way to get there, and it's a way that I love, and I'm happy to put time into trying to get there through encouraging the use, as I say, of language to express the "something" that's not a policy statement, not a rant — except there is a form of poetry called rants — but just not the kind of anger, just sort of gratuitous anger that we so see everywhere. Let's peel this onion. Let's get behind it.

Life Is Uncertain

by Ellen Waterston

All he wants, when surveying the windrows, the fresh bales,

when nursing purpled nail and blistered palm, is to know she'll

be waiting for him at home in the evening and he can ask her,

Do you remember...

When last February's record-breaking snow buckled

the barn roof, the melt flooding the fields and filling

the daylight basement? How he joked he had to swim

to bed, wear irrigation boots to shoot pool?

When the Pandora moth carcasses were so thick

last June they piled up like snow drifts under

the streetlights in town, the wings and antennae

like frail dusky ferns on the pavement?

In August, when the swallows suddenly left, their acrobatics and tart

chirps no longer spicing the evening, their empty mud-daub nests

like featureless faces mouthing no, no? How bereft he was, rattled,

to see them go. No sign of them since or now.

When the greasy smoke from the forest fires never lifted all fall, the water

in the swollen reservoirs and nursing rivers recruited until dry, the sun

an angry orange coming and going in the sky, throwing bloody flames when

eclipsed by the moon? How he'd shuddered at the sudden darkness and cold.

Or when the Pioneer Saloon stopped serving dessert, not even

spoon cake? How, without dessert, without anything sweet,

the way the world was going to hell in a hand basket, he didn't

know what to eat first. He wasn't joking anymore.

All he wants, when surveying another season, is for her to be

there, waiting for him at home in the evening and he can ask,

Do you remember when...we couldn't have said any of this?

She'll take his calloused hand in hers and nod and say yes.

-From the author: "Life is Uncertain" addresses the sense of helplessness and the need to feel safe in the face of climate changes...in this case relative to events that have occurred in the high desert.

Designed to Fly

by Ellen Waterston

After ten hours of trying

the instructor undid

my fingers, peeled

them one by one

off the joystick.

"You don't need

to hold the plane

in the air," he advised.

"It's designed to fly.

A hint of aileron,

a touch of rudder,

is all that is required."

I looked at him

like I'd seen God.

Those props and struts

he mentioned, they too,

I realized, all contrived.

I grew dizzy

from the elevation,

from looking so far

down at the surmise:

the airspeed of faith

underlies everything.

Lives are designed

to fly.

-From the author: "Designed to Fly" is a metaphorical invitation to loosen our grip, to relinquish control ever so slightly and see what happens.