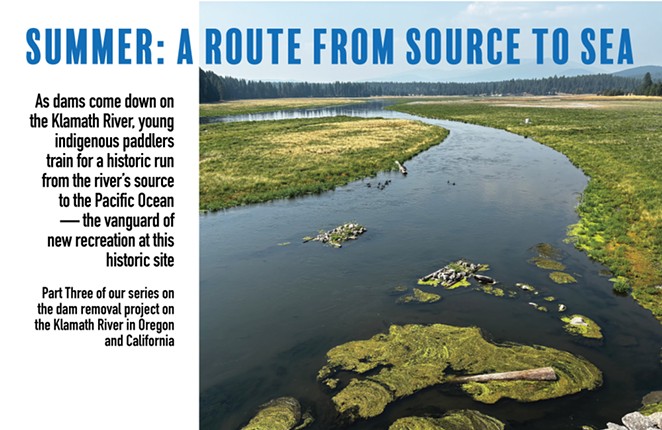

On a recent July day, a group of young indigenous paddlers gathered in Klamath country to train, their sights set on running the Klamath River not far away.

In a matter of a few short weeks, this river will run free all the way from Klamath Falls to the Pacific Ocean. As soon as this autumn, salmon are expected to move up past the old dams. And next spring, while the spring chinooks swim up from the sea and the fall-spawned salmon move down, those paddlers will aim to be the first people in the modern age to descend this stretch of water, from near its source all the way to the Pacific.

As these young kayakers spend their time preparing their boats, bodies and minds for that historic month-long paddle, all along this "hydro stretch" of the Klamath, excavators and loaders, bulldozers and backhoes are hard at work, laying the groundwork for the journey.

This summer, a new version of recreation is coalescing on the Klamath. By next summer, it should be in full swing.

The Ground is Laid

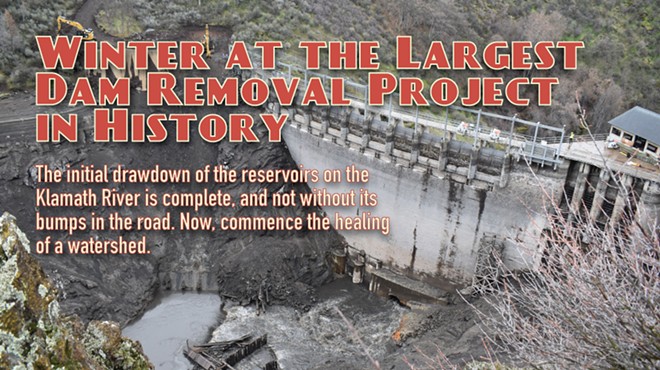

Dam removal has been underway along the Klamath River since last summer, when the first of four dams slated for removal, Copco 2, was deconstructed. That was followed by the drama of "drawdown" in January, when crews drained the reservoirs behind Iron Gate, Copco and JC Boyle dams.

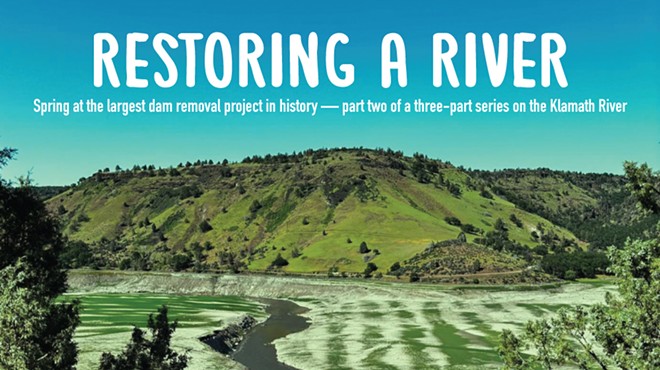

Those were historic moments, but at JC Boyle — the only Oregon dam to be removed as part of the work of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation — another big moment just happened July 30. That's when crews took apart the cofferdam, constructed in the 1950s, to divert the Klamath through the JC Boyle dam. With a few swipes of a long-armed excavator, water began to flow free through that stretch of the Klamath for the first time in decades. Within minutes, excavators were hardly needed; banks began to fall into the water, the river beginning its mighty push on its own to return to its original path. Within weeks, crews told me, they'll have the concrete shell of JC Boyle Dam completely removed.

"JC Boyle Dam was an earth-fill dam with a concrete spillway," described a press release from the KRRC, the entity formed to remove dams and restore volitional fish passage through the Klamath. "The earthen portion of the dam extended over the original path of the river, while the concrete portion was constructed outside the river's path."

Seeing the dam removed and the water flow free was an emotional moment attended by a number of tribal members, KRRC Public Information Officer Ren Brownell told me. Some, who have witnessed the ups and downs of attempting to remove these dams for the past 20 years, said they wouldn't believe it was actually happening until they saw it with their own eyes. Some of those in attendance remembered when the area around JC Boyle was a tribal fishing site. Some undoubtedly hope to see it become one again.

"While there is still work to be done, today is a historic day for this reach of the Klamath River," said Mark Bransom, CEO of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, in a press release. "It was an honor to be able to witness this reach of river coming back to life alongside area Tribes. Each milestone brings the river into a healthier state."

"It could have just been — could be a bunch of white guys that make the first descent of the Klamath, because in modern times, there hasn't been a descent. But why not it be tribal youth?" —Weston Boyles

tweet this

The first descent

Like any form of recreation, there are those who seek to be first — first to summit a peak, first to finish a race. On the Klamath, the group of indigenous paddlers aim to be the first in the modern age to travel the historic Klamath from source to sea.

The effort is being organized by Ríos to Rivers, a nonprofit whose mission, "inspires the protection of rivers worldwide by investing in underserved and Indigenous youth who are intimately connected to their local waters and supporting them in their development as the next generation of environmental stewards."

"First descents are a thing in the kayaking and rafting world — it's very similar to climbing a peak," said Weston Boyles, founder and executive director of Ríos to Rivers. "It could have just been — could be a bunch of white guys that make the first descent of the Klamath, because in modern times, there hasn't been a descent. But why not it be tribal youth?"

Indigenous communities historically used the Klamath for trade and transport, Boyles pointed out, so in that sense, "it's the first modern descent."

Ríos to Rivers began working in the Klamath area in 2017, when dam removal was still a long-hoped-for dream. The organization later formed Paddle Tribal Waters, a kayak and river advocacy training program for youth in the Klamath Basin. The goal: that first descent of the Klamath in spring 2025. The program began with a cohort of 15 youth. This summer, it was training its third cohort — all who aim to be part of the first descent.

For Danielle Rey Frank, director of development and community relations for Paddle Tribal Waters, who is a Hupa tribal member and a Yurok descendent, being "first" is just a small part of the story.

"We have a really long-term goal of having indigenous-led paddle clubs in all the tribal regions in the Klamath Basin as well, so that moving forward, kayaking is something that our people can teach each other." —Danielle Frank

tweet this

"We have this short-term goal of paddling the river from source to sea, but we have a multitude of goals, including sharing the story of how we got to this point with our kids, and helping them understand their role in community," Frank told the Source Weekly.

The fight to have the four hydropower dams — which stymied salmon and caused proliferations of toxic algae in the reservoirs — has largely been led by tribal communities, Frank pointed out. In this next chapter, leaders at Paddle Tribal Waters want students to understand that they're being nurtured into the roles of river stewards, culture-bearers and indigenous leaders.

"We have a really long-term goal of having indigenous-led paddle clubs in all the tribal regions in the Klamath Basin as well, so that moving forward, kayaking is something that our people can teach each other."

With algae-promoting reservoirs now gone, and salmon expected to begin returning in the fall, Frank and others hope to see tribal communities use the river recreationally moving forward.

"Historically, it's been really out of touch for us. It's been something that we just can't quite obtain, due to the cost and the lack of knowledge and training," she said. "And also, a little bit of a disconnect between the average whitewater world and our communities. You know, there's a lot of people who get into kayaking to become stewards of the land and try and best understand how they can help support these river basins and help support the waters. And then with us, water transit has been something in our communities that's existed since before time — we've had canoes up and down this river."

For Frank and others, this entire effort is about healing.

"There's definitely some issues in our communities right now due to the generational trauma that we've experienced. But I think this is the best healing pathway that we could be on — right along our river. I truly believe that as our river heals, our people will as well."

Frank and Boyles say the first descent will include the youth who have taken part in the training program who wish to take part. At stops along the way, they'll join tribal communities for cookouts and other celebrations aimed at marking the historic journey. While the date has yet to be set, Paddle Tribal Waters is looking at a late-spring departure date for the first descent trip.

Planning for Recreation

The stretch of Klamath River between Klamath Falls and Iron Gate Dam, the westernmost dam slated for removal, hasn't been entirely devoid of recreation in its years as a center for hydropower — but things are certainly changing. Reservoirs that once hosted motorboats and revelers are now gone. A stretch of river downstream from the JC Boyle Dam that once boasted big flows due to dam activity, called Hell's Corner, won't flow as mightily anymore — a point of contention for some in the whitewater community. (Editor's note: this section has been updated to indicate that it's the Hell's Corner, not the Big Bend, area that will no longer have high summertime flows. We regret the error.)

Still, other stretches might make up for it, said Scott Harding, stewardship association for American Whitewater, a national nonprofit that advocates for the preservation of whitewater rivers in the U.S. Harding's organization has been a player in ensuring that recreation sites along the newly exposed stretches of the Klamath are safe, and accessible.

Whitewater enthusiasts are looking at Ward's Canyon, a 3-mile stretch of Class IV rapids that could be Class V with dam removal. American Whitewater describes it on its website as "a scenic and geologic wonder with the utmost significance to the Shasta people, a 300-foot-deep defile bounded by sheer colonnades of columnar basalt unlike any other on the Klamath River."

"Now we can return home, return to culture, return to ceremony, and begin to weave a new story for the next generation of Shasta, who will get to call our ancestral lands home once again." —Janice Crowe

tweet this

Ward's Canyon is located in the stretch of the Klamath that in June was promised to be returned to the Shasta Indian Nation. On June 18, California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that the state of California would return some 2,800 acres to the Shasta people.

"The Shasta Indian Nation is comprised of people who came from the villages of Kikacéki, a reach of Klamath River which spans the Copco and Iron Gate reservoirs and has been either dewatered or covered by reservoirs for over a century," stated a press release from the Shasta Indian Nation.

"Today is a turning point in the history of the Shasta people. The story of what Shasta people and Kikacéki have experienced over the last 150 years has been a painful one to tell. For so long we have felt a great loss, a loss of our family, our ancestors, for the loss of our villages and ceremony sites," said Janice Crowe, Chairman for the Shasta Indian Nation. "Now we can return home, return to culture, return to ceremony, and begin to weave a new story for the next generation of Shasta, who will get to call our ancestral lands home once again."

The lands that will be returned to the Shasta people also include the Copco Village, including the still-standing Copco No. 2 powerhouse which will be converted into an interpretive center that tells the history of the Shasta people, the dams and the story of the river, the tribe stated.

Those lands are among the 8,000+ acres of land to be surrendered by PacificCorp under the dam removal agreement. Who will ultimately steward the remaining lands is still unknown. On the Oregon side, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife will make the call.

According to Harding, when crews finish remediation of the sites around the dams, they'll begin work on five river access facilities that will breathe new life into recreation in the area.

"There's a remarkable transformation going on here. We're not just looking at four dams being removed and their associated reservoirs and the river coming back. There's also a transformation in the way that you can go and experience the place," Harding told the Source Weekly. "One experience is to go to a reservoir and recreate there or spend time there. And there definitely were recreational opportunities on these reservoirs that help people enjoy, that will no longer exist. It's another thing to be able to go to a restored river system and watch that process take place, right?"

Some of those who live along the shores of the former Copco Lake, like real estate agent Danny Fontaine, say they look forward to new recreation opportunities — and dispelling the rumors that have proliferated about what happens with dam removal. As part of the agreements dictating what happens on the Klamath is a caveat that the lands surrendered be slated for public use and recreation. But some residents, he told me, still fear that they won't have access to the river once the lands are doled out.

"You can hear the rapids from your house, from our deck," Fontaine described when I talked to him in May. "The potential for rafting trips down through here, and recreation of that sort... fishing comes back. They're not gonna keep us from the water, like the rumors and all that. They're not gonna keep people away from the water and stuff like that, like all the rumors."

Eyes on the Water

Farther down the river from the dam sites, more eyes are turned toward the water. This month, the Karuk Tribe slipped a dugout canoe into the Klamath River for the first time in 60 years. Environmental and political challenges had left the tribe without its important water tradition for decades. For one, the tribe doesn't have its own lands — so no place to harvest the sugar pines necessary for the canoes. In 2019, tribal member Adrian Gilkison began to raise funds to build three boats. He died before seeing the project come to completion, but his son, Grant Gilkison, took up the charge, as Jefferson Public Radio reported. Volunteers finished the first of three canoes in May, and put the first páah, or canoe, into the water at the Orleans bridge — another sign of healing along this river.

Momentum is happening with river restoration in this entire watershed, too.

As Anne Willis, California regional director of American Rivers told me in January, her organization is among those eyeing the tributaries of the Klamath.

"The Shasta River, the Scott River, the Trinity River... all of these rivers have been impacted, not so much by dams, though, I would say arguably, the Trinity, absolutely," Willis said. "The Klamath is like the highway, and these tributaries are like the bedroom communities that these salmon go to, to spawn and rear and before they go out, migrate back to the ocean. And so I'm already working with some landowners and some of these tributaries, setting up collaborations and partnerships with some of the local tribes, and specifically the Yurok tribe, so that we can facilitate river restoration, river conservation on the tributaries."

The Work Starts

Forward thinking — to next year's descent, to the return of salmon, to how the eyes of the world will regard this historic project — is the name of the game for so many involved on the Klamath River today.

"I feel like my whole life has been surrounding the Klamath dam removal movement. And now it's happening," Danielle Frank of Paddle Tribal Waters summed up. "We always say that once the dams come down is when the work really starts. Because there's decades of restoration to be done, for our culture, for our people and for our river."

Read parts 1 and 2 of our series on the Klamath River dam removals: