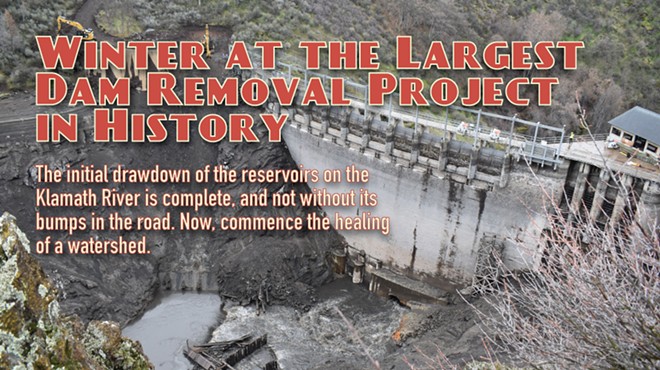

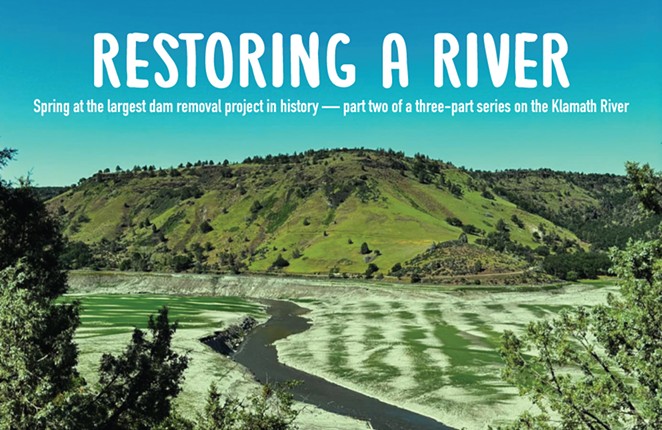

We're pulling up to the offices that sit above Iron Gate Dam, now more of a shrinking pile of rubble than a tool of impoundment for millions of gallons of water, when I notice that the map in the truck, showing us how to get there, is no longer accurate. On the screen is a wide, blue reservoir rather than a squiggly strip of river, as the Klamath River now appears in real life.

Consider it just one of many adjustments the world needs to make around the largest dam removal in U.S. history.

This winter, I traveled to Iron Gate Dam to walk on its expanse one last time as the reservoirs drained; as Iron Gate and Copco lakes said their farewells to the world. I wanted to see for myself how a river was snaking itself through the landscape while those former reservoirs flowed out to the Pacific Ocean.

Now I'm back to witness the rebirth of a watershed — to see how that river has shaped up, and how thousands of acres of banks surrounding Koke — the Klamath word for the river — are emerging from their decades underwater.

Drawdown — the act of draining those reservoirs — was the sexy stuff that garnered headlines around the world at the start of this year. When non-native fish began to die from that process, and when a grouping of wells dried up around Copco Lake, opponents of this project crowed their told-you-sos.

This spring is a bit less flashy. Every day, some 400 truckloads of materials are hauled out of Iron Gate Dam alone. It's a slow, plodding process, removing the dams bit by bit so as to preserve water quality as much as possible in this long-turbid river.

The miracles of the restoration process are more of a slow burn — clusters of California poppies bursting through the dried mud; tiny acorns planted by Native crews beginning their slow reach toward the sun.

As crews chip away at removing the Iron Gate, JC Boyle and Copco I dams, on the banks, crews from the Yurok Tribe, working with the country's largest ecological restoration company, Resource Environmental Solutions, are hard at work replanting. Spring is an ideal time to begin to see nature taking its course — with a lot of help from a replanting project, years in the making.

'A biological need to be here'

Richard Green is a member of the Yurok Tribe and a revegetation field lead with the tribe's planting crew, contracted by RES to plant thousands of pounds of seeds and starts along the newly exposed banks of the Klamath River.

The Yurok traditionally lived west of the dam sites, but as a tribe that made its home along Hehlkeek 'We-Roy — the Yurok term for this expansive river — its members were keenly interested in being part of its restoration and recovery. Yurok revegetation crews, consisting of both Yurok and Karuk tribal members, got started years before drawdown became a distinct reality, recovering native species in the watershed, collecting their seeds and delivering them to nurseries in southern Oregon. There, seeds became starts that were delivered back to planting crews to get into the ground. All told, some 90 native species are being replanted here.

"I've seen people in my tribe work for the restoration of this river for over three decades — and it's been going on long before that, too," Green told the Source Weekly. Green's grandmother was also an advocate for the river, serving on both the tribal council and as a tribal representative, advocating for the river in Sacramento as well as Washington, D.C. She passed before knowing the dams were officially set to come down, Green said.

"Everyone has a biological need to be here. It's a hard job – pretty brutal work, but everyone does it with a smile on their face when we're there." —Richard Green

tweet this

"I think she'd be pretty happy to see this level of action taking place," he said. "It's not just the dams, but the restoration as well."

Green said he and his colleagues often get asked why they don't just let nature take over more organically — why the massive effort at replanting?

"If they would have just let the area go, it would be inundated with invasive species — a monocrop in the area," he said. "We put a good deal of effort into adding lot of diversity in the replanted areas."

With some 17 billion native seeds going into the project, it's hard work for the replanting crews, Green said, but the meaning overshadows the long days.

"Everybody on the crew is either Yurok or Karuk – coming from this river," Green said. "Every one of them grew up on this river and have seen this roller coaster of events just within our lifetime. Everyone has a biological need to be here. It's a hard job – pretty brutal work, but everyone does it with a smile on their face when we're there."

Getting it right

The first dams on the Klamath River were built to provide hydropower for the area just over 100 years ago. They began to come down in 2024 after decades of advocacy by local tribes, scientists, community members and political leaders, culminating in a unique agreement between PacificCorp, the states of Oregon and California and a long list of signatories. The Klamath River Renewal Corporation was formed in 2020, tasked with overseeing dam removal.

A portion of the $500 million cost of removing the dams, around $215 million, was passed on to PacificCorp's ratepayers. But in the end, that was the less-expensive option, compared to the cost of adding fish ladders to each of the four dams now in the process of removal, according to PacificCorp. With the dams providing less than 2% of the utility's power supply, the electricity was easily replaced.

During the past century, water quality has suffered. Toxic blue-green algae — mostly the liver toxin, microsystis — and invasive species have proliferated in the area. Salmon have literally been filmed beating their heads against the concrete of Iron Gate Dam, hoping to travel to upstream spawning areas, according to Dave Meurer, director of community affairs for RES.

With all of that, fixing what's broken won't happen overnight.

"If you consider dam removal the surgery on the Klamath River, consider restoration the physical therapy," Meurer told the Source Weekly. "And it is going to be a long time — the patient has really been through something. . . an ordeal."

Like the Yurok replanting crew, Meurer said he, too, often gets asked why there's been so much effort put into the replanting.

"If we let nature take its course, it would be a field of star thistle, cheat grass and medusahead. This area is full of invasive exotic vegetation. So our job is to give the native plants a head start, before those invasives try to move in," he said.

RES is in it for the long haul, setting a several-year timeline for restoration efforts.

"We guarantee the performance of the site," Meurer said. "And that means we have agreed in advance with the client and with regulatory agencies about what success looks like. And we don't quit until those metrics are [met]."

Guaranteeing success on a project on land you can't yet see is a big challenge.

"Number one, the area we needed to restore was underwater. So it was invisible to us. We're having to plan on something we can't see. So we did have historic photos, we had lidar available... we had a good idea of where the river used to be, had some good historic photos. But we literally had to be planning for something that would only be revealed this past January," Meurer said.

"We did as much planning as we could — about a 60% design and had a conversation with the regulatory agencies — look, we can't tell you exactly what this is gonna look like. Because we don't know. And we're not going to say hard and fast, here's where a tributary is going to be. Because we need to see what happens. Where's the water want to go? So it was a different process than we were used to."

RES, whose experience includes massive projects in places like the Chesapeake Bay, made the call that for the Klamath, they'd focus mostly on the "high priority tributaries," letting the main stem of the Klamath recover on its own.

"In August, the water smelled terrible," Fontaine said. "There was a lot of algae, and it would get stuck on your boat propellers and things like that."

tweet this

In the end, nature sets the timeline.

"We don't decide when the project is done," Meurer said. "We replant everything, we re-vegetate everything, but we have agreed in advance with the regulators and with the client — what does success look like? What does the ground cover look like? How are things growing? Is volitional fish passage available — can fish pass freely back and forth? Are there any barriers that need to be removed? So once the standards are met, figure maybe in a five-plus year timeframe... only when the site is on positive trajectory and growing well, will we be released from our obligation. We won't have to babysit the site anymore. But until then, we own it. Good, bad, beautiful or ugly."

In a dry, fire-prone area, that guarantee means that should a fire and a flood hit the area, RES will come in and start over.

Year one of replanting, which started mere hours after drawdown of the reservoirs began in January, has thus far been more successful than RES hoped.

"We're very, very happy with how things are growing," Meurer said. "You will see that some areas took better than others. And that's not unexpected. Conditions vary. Some areas were planted by hand; some were planted by helicopter. The crews planted as much as they could by hand, but the sediment was very, very moist. And it was like quicksand on part of it."

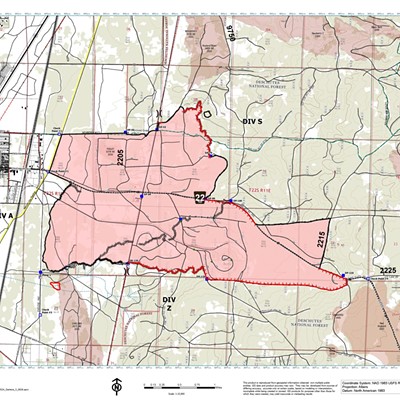

In the areas around the former Copco Lake reservoir, the replanted areas appeared in mid-May as striped portions of green — evidence of where helicopters were employed to drop seed in a muddy area not accessible by ground crews at the time.

"Our goal is to come back this fall and finish the rest of the landscape entirely with the rest of the seed we've collected before this," said Green, of the Yurok planting crew. "And then there will be ongoing maintenance beyond that."

"In addition to being our revegetation seed harvesting crews, the Yurok are also our invasive exotic vegetation, IEV control crews," Meurer said. "So, for years and years before drawdown, they were out here with weed eaters and by hand treating the area for those, to create a buffer between the reservoir and the invasive species. They've done a really good job of creating a buffer zone between the aggressive weeds and the new plantings."

A community in transition

The helicopter-generated, striped pattern of green and brown, surrounded by a snaking river, is the present view for those who live in the town of Copco Lake. Many here bought their homes specifically to live on a lake that no longer exists — so the changing reality has been tough.

Danny Fontaine, a local real estate agent and the owner of the local store (currently not open), and his husband bought their home in Copco Lake in 2014, enjoying many years of lakeside living before the reality of dam removal set in.

"Devastation, depression, anger," is how Fontaine described his initial feelings about dam removal.

"We would go out on the water, on a sunset cruise — we miss that. We'd watch the sun go down from the boat... we'd fish off the dock, catch a load of fish and have a fish taco night down there in the backyard of the store." —Danny Fontaine

tweet this

"Every night we used to go out there," Fontaine recalled of lake days before drawdown. "We would go out on the water, on a sunset cruise — we miss that. We'd watch the sun go down from the boat... we'd fish off the dock, catch a load of fish and have a fish taco night down there in the backyard of the store. Having the docks right there where you just walk down to your boat from your house is nice."

If that sounds idyllic, it was, of course, tempered by water quality issues and toxic algae in the lake.

"In August, the water smelled terrible," Fontaine said. "There was a lot of algae, and it would get stuck on your boat propellers and things like that." With that, recreation activities like boating and fishing suffered, Fontaine said.

"During the summertime on a holiday weekend, if we had the lake there right now, it's Memorial Day weekend, we would probably have maybe... the most was three to four boats out there on the water at any given time."

The devastation Fontaine felt at the announcement of dam removal eventually morphed into resignation, he said, and later, interest.

"It was a really nice place," Fontaine told the Source Weekly. "That being said, once the decision was made, we — my husband and I — both just said, you know what, they're going to do this; it's a good decision, too. The government's behind them, they're supporting it, there's no way that this is going to be reversed. So we need to learn to live with it instead of having it destroy our life."

The decision to accept the reality of dam removal has put the couple at odds with some of their neighbors, Fontaine said. "Other people that live out here — it's destroying their happiness; it's destroying their daily life... because there's a few people that it just consumes their everyday world."

Hardships have popped up for community members. Two wells servicing 11 homes dried up post-drawdown — an effect currently mitigated by the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, which is footing the bill for water for the 11 houses while they work on a larger plan, KRRC Public Information Officer Ren Brownell told me during my January visit.

"They're not just leaving people without it," Fontaine said. "Other people are complaining — they're complaining and bitching about it. But they're [KRRC] still taking care of it for them. So that to me is a positive thing."

"In the last 100 years, salmon runs have declined by about 98%, which is moving dangerously close to extinction. So, we are actually in a race against extinction. We know what the stakes are." —Dave Meurer

tweet this

As a real estate agent, Fontaine said he has not seen a massive outflux of people selling their homes now that the lake is gone. Property values have also held, Fontaine said.

Early in the process, some property owners' values did drop, according to 2012 reporting from the Herald and News in Klamath Falls.

In 2024, Fontaine isn't seeing massive value drops — perhaps due to the potential for new types of recreation along the Klamath.

"The way that the river is running through here... you can hear the rapids from your house, from our deck. And the potential for rafting trips down through here. And recreation — fishing comes back." With the lands exposed by drawdown slated to be returned to public use once restoration is over, Fontaine said he's also not concerned about seeing access to the river limited.

High stakes

As summer approaches, the light-green plants that populate this new version of the Klamath River will undoubtedly dry out in the heat. Acorns will turn to oaks ever so slowly. Poppies that presently bloom bright orange will shrivel back — as flowers often do in summer. These rhythms of nature will surely bring out the naysayers; the ones convinced this massive project will fail.

"This is the largest combination dam removal and river restoration project ever undertaken," Meurer of RES said. "It's exciting to be the restoration contractor. And we know that the eyes of the world — literally the eyes of the world [are on us.] BBC was out here last week. We've had The Guardian report on this. We've had Canadian Broadcasting Corporation out; The New York Times was out recently. The interest is understandable, because the Klamath was once the third- largest salmon-bearing river in the West. And in the last 100 years, salmon runs have declined by about 98%, which is moving dangerously close to extinction. So, we are actually in a race against extinction. We know what the stakes are."

Indigenous names for the Klamath River:

Ishkêesh – Karuk

Koke – Klamath

Hehlkeek 'We-Roy – Yurok

Read part one of the series: