It was a recent day in June. On an island of manicured grass surrounded by undeveloped land, Oregon State University-Cascades held its graduation ceremony.

"Think about it. Think about all the work you've put into arriving at this moment," said Kimberly Howard Wade, executive director of Caldera Arts, to the field full of students in black robes. "You've learned how to go from concept to completion. From wonder to tenacity," she continued in her commencement address.

A few seats down from the podium where Wade stood, Christine Pollard, OSU-Cascades' newly minted senior associate dean, nodded, a half-smile on her face. In front of her sat 44 doctoral students – the first doctorate of physical therapy class to ever graduate from a public university in Oregon. The first time the school has ever hooded doctors.

Their presence was a direct result of her work: her ability to go from conceiving of the state's first doctor of physical therapy program at a public university to realization. A concept 20 years in the making.

From the Court to the Classroom

Growing up in Eugene, Pollard enjoyed sports and time spent outside. Basketball was a passion. Her ability on the court and love for sports led her to Azusa Pacific University in Southern California, where she played ball for the school while studying kinesiology. She was the first in her family to attend college.

"My parents didn't go to college, so I was a first-gen student. That kind of relates to my passion for OSU-Cascades," Pollard told the Source Weekly. "I had no idea how much I would learn from college about myself and my capabilities, both inside and outside of the classroom. In reflection, one of my biggest joys is creating this experience for the next generation of students."

APU was also where she had her first experience with physical therapy when she saw teammates treated for anterior cruciate ligament tears. This type of injury can occur when the knee is stretched too far, and is among the most common of knee injuries. Knee injuries would end up being a phenomenon Pollard would research for years to come.

Having graduated with a degree in kinesiology, Pollard decided to study physical therapy at Pacific University in Oregon. From there, she earned a Ph.D in biomechanics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, eventually teaching at one of the top PT schools in the nation, the University of Southern California. During this time Pollard questioned the lack of a similar program at a public university in her home state. Going out of state or attending a private school were the only options for Oregon students at the time. And, only two private schools offered physical therapy degrees, making it an unattainable career path for many, since the cost of schooling could balloon to two to three times as much as an in-state, public university.

"When I was there, what I realized was that all of the students from Oregon were coming down to USC and these programs in California," she said. "And, so I really got interested in why Oregon doesn't have a public institution DPT program."

Persistent Questioning

"When I got here in 2011, I asked the dean of the [OSU] College of Health in Corvallis, 'Why don't we have a physical therapy program at OSU?'" Pollard said, finally posing the question that had nagged her for years. She learned many had tried, and failed, because the amount of time, work and financial support to create a program was too intensive. And, if she wanted to tackle launching a new degree program at OSU, there was a tall hurdle ahead.

"She said, 'Get tenure, and once you get tenure, then we can talk more about it. Focus on getting tenure,'" Pollard recalled.

The path to tenure at an academic university varies, but it is rarely easy, and not guaranteed. OSU's faculty handbook describes it as "awarded only after an extensive probationary period, during which the highest standards of scholarship, teaching, and service must be demonstrated to the satisfaction of local peers as well as nationally/internationally recognized experts."

Resolute in the interim, Pollard continued sowing seeds that would grow to root the DPT program to come. In 2011, upon joining the staff to launch OSU-Cascade's first kinesiology program – with just seven students – Pollard went about creating a proper lab for studying kinesiology and conducting research. The school was only 10 years old and housed at Central Oregon Community College's campus, so Pollard teamed up with specialists at Bend-based The Center Foundation and Therapeutic Associates Physical Therapy, and the Functional Orthopedic Research Center of Excellence, known as the FORCE Lab, was born. These early efforts and community connections would prove vital to Pollard's later development and implementation of a "modernized" DPT program.

OSU-Cascades moved to a permanent campus five years later, with a long-term plan to grow to accommodate up to 5,000 students. Billed as Oregon's first new public university campus in more than half a century, the school sits on 128 acres, including a former pumice mine and a demolition landfill. Its opening was a significant development for the school and the state. It was also an opportune time for Pollard. She was tenured and ready to raise the idea of a DPT program again. This time the buy-in was there.

She got the green light to pursue the program, but there were still years of strategizing and planning ahead. A donation in the spring of 2019 allowed Pollard to step out of the classroom and focus on building the DPT program. Then COVID hit.

"A lot of the design happened in the pandemic," Pollard said. "I'll forever remember me and my Bernese mountain dog sitting in my home office, spending all this time developing the program." That downtime, when so many teachers were working from home, too, meant easier access for Pollard to colleagues at PT schools nationwide. They would talk about the best way to build a program from the ground up, how modern concepts and technology could be baked into the design and what would be best to emphasize within it.

"It was really fun, and I think that we're still enjoying that process because we still have a lot of flexibility in how we think," Pollard said. It also meant that word of the program spread, and top-tier teachers were interested in taking part.

New Buildings and New Tech

At the OSU-Cascades campus today, the sounds and sights of construction permeate. So far, 13 of 128 acres have been developed and a 10-acre land remediation is underway on the former demolition landfill area. A new building going up will be a Student Success Center. Next door to it Edward J. Ray Hall rises — wood, metal and glass off the leveled landscape.

The hall was completed in 2021 to the tune of $49 million. It's powered by geothermal energy, courtesy of an aquifer 500 feet below ground and built with timber from regional forests – all part of the campus' long-term goals of being net-zero in energy, waste and water. Among the initiatives it houses are the DPT program, the new state-of-the-art FORCE Lab and a cadaver lab. It was designed with input from Pollard and DPT faculty and includes a double-sized classroom with 24 treatment tables for students to practice on one another and a clinical skills classroom where students can train on commonly used physical therapy equipment.

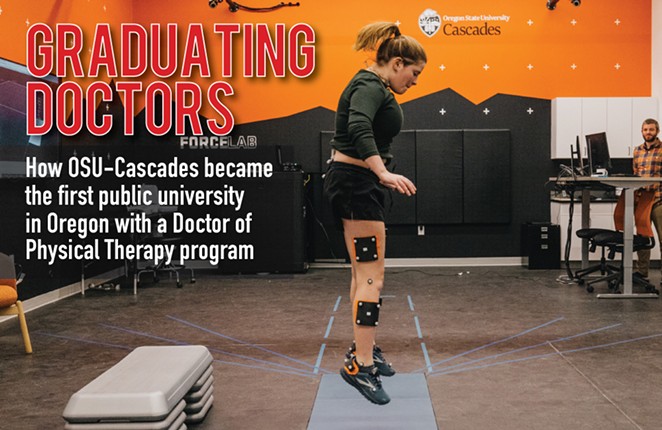

At the bottom level of the building is the FORCE Lab. It's an extra-long rectangular room with the vibe of a hip, high-end workout studio. On one end, two walls are painted OSU orange with large black triangular silhouettes, reminiscent of mountains at sunset. Tracks for cameras run above, alongside the exposed piping, and a large television is mounted opposite a standing desk outfitted with multiple computer screens. Inset in the floor are three large plates to measure the force and movement of subjects.

To quote the Little Mermaid, they've got "gadgets and gizmos a-plenty," along with "whozits and whatzits galore." There's a 10-camera 3D motion capture system. There are two high-speed video cameras that can sync with the 3D kinematic data, an eight-sensor wireless electromyography system to measure muscle activation, wireless insoles to slip into your shoes to map where your foot puts pressure during dynamic movement, a biodex dynamometer to determine muscle strength around any joint, sophisticated tracking and modeling software and much more.

On one visit to the lab, JJ Hannigan, an assistant professor in physical therapy and the lab's co-director, walks me through some of its capabilities. In addition to running the lab and teaching, he conducts research there. A couple of recent studies, one looking at the impact of minimal-style running shoes on youth and the other researching how maximal running shoes affect runners' form have garnered media attention at the local and national level. During our talk, Hannigan stresses the importance of exposing DPT students to research. Each student in the three-year program must work on a capstone project — research led by a faculty member during their second year.

"One of the goals of our program is to train clinician scientists, those that aren't just well-versed in treating patients, but folks or clinicians that are able to engage a scientific process while they're treating folks," Hannigan said. "They can look at a research study and better understand the steps the researchers went through. They have a better lens of looking at maybe limitations of that research and seeing what they could or couldn't apply to their clinical practice."

The requirement of a capstone project is one of the unique aspects of the program. So is the opportunity to study human anatomy and the skeletal and muscle structures on cadavers. That lab is run by Kathryn Lent, an assistant professor in the DPT program.

"We're very, very grateful to have that opportunity to learn from human tissues and from the donors themselves. And grateful to the donors and their families for this opportunity," she said.

Lent joined OSU-Cascades in 2021. Before that she was at the University of Washington. She said the chance to help mold the program was a key reason she joined the school.

"I think one thing that drew me to this particular program was the newness," she said. "Being a part of creating something from scratch is pretty special, and the opportunity for that doesn't come up that often. We can literally create the curriculum and the mission and the culture around here. I jumped at that opportunity."

Another reason, she said was Pollard. "I think seeing the work that she had done, and talking to her about the process of creating this program, knowing that she was from Oregon...I think was also a big draw."

The other significant ways that the program stands out, according to Lent, and other faculty members and students, is in its robust clinical rotations that start in year one, its emphasis on rural care and its approach to diversity, equity and inclusion.

Each cohort of roughly 45 students rotates between taking classes on campus and clinical rotations. Those rotations start in year one. This is where the importance of a strong physical therapy community around the school matters, and what Pollard was hoping to foster decades ago, when she first broached the idea of a program in Bend. Chalk it up to the active lifestyle of people in the region, but Deschutes County has more physical therapists per capita than anywhere else in the state, with 1 PT for every 783 people. The state average is 1 for every 1,413, according to the Oregon Health Authority's most recent estimates.

"There are so many PT clinics here, and physical therapists in general," said Collier Lawrence, a third-year student and former professional runner who's lived in Bend for the last 10 years. "They also have to be behind this program, because it really takes the whole community to be like, 'Yeah, you're going to have 40 students in a cohort, 45 students, and there's going to be a clinic for every single student's rotations.' That's a really big aspect."

At this point, just a few years in, and having graduated the first cohort only a couple of months ago, the program is clearly popular. Applications far outnumber spots. According to the school, it receives as many as 10 times the number of applications as there are spots available. Of those applicants, 150 will go on to virtual interviews (all are virtual to ensure equity and fairness in the process) and roughly 45 will be offered a spot. The faculty includes experts who came from schools around the country and two dozen lecturers from the local PT community. The program achieved full accreditation this spring – just a month before graduation — and a few weeks ago the first cohort sat for their licensing tests — the final test before they can practice in a clinic. Pollard says half the class has job offers already, several of them in very rural areas in Oregon and many at multiple clinics.

"They made us so proud," Pollard said. "I mean they really did. Knocked it out of the park."

Meanwhile, Pollard has pivoted her focus to her new role as associate dean. In the last eight months, she created a new leadership structure on campus and hired heads of each education program. Next on her list is continuing to grow the campus, adding more students to more programs and completing buildings like the student center going up outside her office window. However, on a recent trip to campus, Pollard was drawn away from her desk to check out the DPT classroom and the FORCE lab where she greeted DPT and undergraduate students by name and was quick to ask about their work and studies.

— This story is powered by the Lay It Out Foundation, the nonprofit with a mission of promoting deep reporting and investigative journalism in Central Oregon. Learn more and be part of this important work by visiting layitoutfoundation.org.