In a Land Birthed by Fire

Part two of a three-part

series exploring how Central Oregon can safely live with fire.

Since May of this year, the Source Weekly has been investigating how prepared the region is for the next nearby wildfire. Part 1, Treating the Forest, looked at fire mitigation efforts in the wildlands around Bend – focusing on a first-in-the-nation pilot program to ignite controlled burns closer to cities, and more aggressively than ever before.

In Part 2, conceived of before the Darlene 3 Fire in La Pine, we dive into attempts at different levels of government to balance wildfire risk with population growth and personal accountability.

On Tues., June 25, shortly after noon, a fire started about a mile southeast of La Pine, on the east side of Darlene Way. Initial estimates by Central Oregon Fire put the size at 3 to 5 acres. By 1:50 pm, roughly an hour later, nearby residents received "Go Now" evacuation orders. People rushed to leave, grabbing the essentials, packing up their animals and heading out of their houses for what could be the last time.

Darlene 3, as the fire would later be named, continued to grow over the next few days as firefighters worked around the clock to establish lines around it and protect properties. The wind whipped but continued to blow away from La Pine and the thousands of people who live there, surrounded by forest. A week later, on Tues., July 2, the fire was 100% contained and all "Go Now" evacuations were lifted. It left nearly 4,000 burned acres in its wake but no structures or lives were lost to its flames.

A positive outcome was far from guaranteed. If the wind shifted, if the response was slower, if previous sections of the forest near town weren't preemptively burned, La Pine may have been lost — another city that by name alone could bring to mind total devastation, like Lahaina or Paradise before it.

For many in La Pine and throughout Deschutes County, the threat of wildfire is a known and accepted risk, a tradeoff one makes to live on the borders of urban and wild. Darlene 3, for all the worry and costs incurred so far, is not an anomaly. The name even speaks to that fact. It's named Darlene 3 because it's the third fire ignited near Darlene Way. The week before Darlene 3 was Darlene 2, put out before it could cause trouble. The original Darlene was in 2021. And the risk of another Darlene, or more broadly, of another wildfire near communities in Central Oregon, is rapidly increasing.

By mid-century, just a couple of decades from now, the annual potential for very large fires is projected to increase by at least 350% over the 20th-Century average, according to the Deschutes County Comprehensive Plan 2040. Wildfire is the second most significant hazard to the county (behind winter storms) and one of the most concerning to the public, according to the county's Natural Hazards Mitigations Plan. With a drying and warming climate, vegetation (aka fuel) will grow more robust during longer growing seasons and further deplete soil moisture. These trends, laid out in the county's comprehensive plan, will mean people living within its borders can expect not just more fires, but more severe fires.

Layered on top of this growing wildfire risk is a population boom. Last year, La Pine was among the fastest-growing communities in the state, according to data from Portland State University, and the county at large continues to grow swiftly.

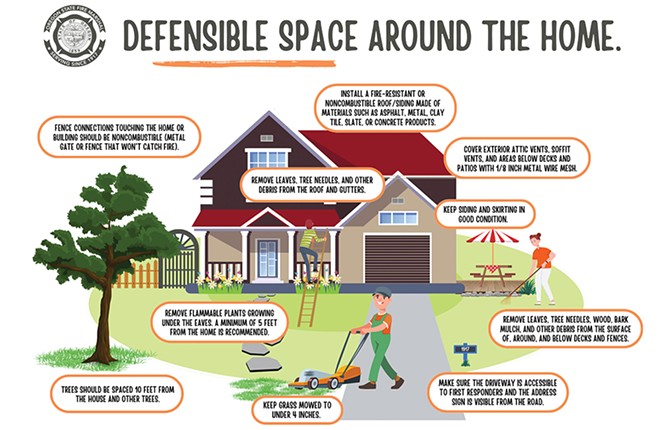

But, experts stress, wildfire risk can be mitigated. Building practices, landscaping standards and regulations on where development occurs can all give homes and communities better chances of surviving fire. Even small changes, like clearing combustible material from the first 5 feet of a property, can net big gains — especially when applied community wide.

In 2021, following the 2020 Labor Day wildfires, which destroyed more than 4,000 homes and killed 11 people across the state, the Oregon State Legislative Assembly took a step toward preventing more devastating losses with the passage of Senate Bill 762. The bill, passed with bipartisan support, directed the Oregon Department of State Fire Marshal to develop defensible space codes and for the Building Codes Division to adopt fire-hardening building code standards; a draft is available online. However, the new measures are dependent on a statewide wildfire risk map. Public backlash to the original map put out in 2022 was sharp and the state quickly pulled it back. That was two years ago.

The second version of the map, now dubbed a wildfire hazard map rather than a wildfire risk map, is expected next month. Meanwhile, new construction continues to go up and another fire season is underway, without any changes that could make communities safer. Even years from now, when the map is finalized and codes and regulations are in place, some worry it may not be enough and that it may be too late for some properties.

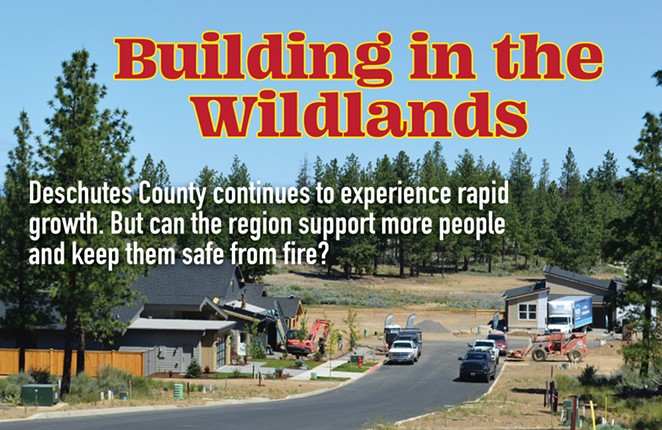

Beauty and Risk in the Trees

Along the northwest side of Bend is a highly sought-after area with hundreds of homes under construction across multiple developments – all bordering trees. A decade ago, most of the area was ineligible for urban development. As that land was brought into the city's Urban Growth Boundary and built upon, it became an extension of Bend's wildland-urban interface, or WUI – areas where human development meets forest or other types of natural vegetation. Pushing out farther into the wildlands increases the risk of wildfire to the community in two main ways: a greater likelihood a fire will start because of a person (around 85% of wildfires are human-caused) and wildfires that do start will now have a greater risk of burning homes.

This trend of building in the WUI is a national one. An often-cited study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that a third of homes are built there, making it the fastest-growing land use area in the lower 48. "Wildfire problems will not abate if recent housing growth trends continue," the study's authors wrote.

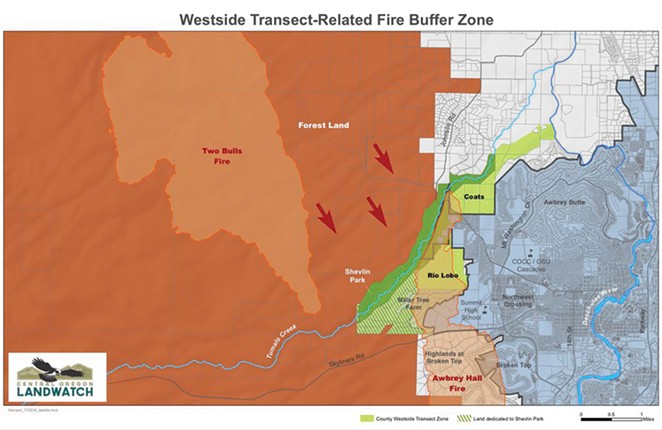

In part because of these reasons, development in the WUI is controversial — a constant push and pull between elected officials, developers, advocacy groups and the public. That tension was made clear in 2009 when city officials proposed adding more than 8,000 acres to Bend's UGB, much of it along the west side. Central Oregon LandWatch, an environmental and land use watchdog organization, challenged the move and led a successful appeal of the city's plan, resulting in significantly scaled-down additions.

"A big reason that we fought against those lands being added to the urban growth boundary was because of the fire risk," said Rory Isbell, an attorney and rural lands program manager with Central Oregon LandWatch, referencing the Awbrey Hall fire in 1990 and the Two Bulls Fire in 2014 that destroyed homes and threatened many more in the same area.

Working with landowners, LandWatch's former executive Paul Dewey helped develop a proposal for a new zone called the Westside Transect. The zone, which is singular in Deschutes County, requires that residential subdivisions have significantly fewer homes than code would have otherwise allowed and that strict fire protection requirements are employed for building materials, landscaping and open space. These changes, experts believe, will give developments in the transect a better chance of survival in a fire.

Builders in one transect development, Discovery West, hired local consulting company Tamarack Wildfire Consulting to help determine a wildfire mitigation plan for the neighborhood. Craig Letz, co-owner of Tamarack and former fire chief for the Deschutes and Ochoco National Forests and Prineville BLM in Oregon led the efforts, ensuring that everything from the type of siding to the exterior vent size and the plants used for landscaping were specifically chosen for their abilities to help alleviate wildfire risk.

"There's always going to be a risk, and we know how to address that risk through our building practices and our landscaping practices," Letz said.

Doug Green, a program manager for the Community Planning Assistance Wildfire Program at Headwaters Economics, agrees that wildfire risk can be lowered and worked with the city and the county in years past to try and develop local codes and regulations.

"We did a report in 2016 that recommended the city come up with some land use regulations and codes for building in high-hazard areas," Green said. "It's been talked about over the years. It's just never, never occurred because of a number of reasons. There's this misconception that it's going to slow development or cost a lot more money to build that way, which has proven not to be true."

Before SB 762 in 2021, Deschutes County was working toward developing its own measures, but that work was set aside while waiting for approval of the state's hazard maps and implementation of pending building codes and requirements. In the absence of regulation, homeowners and neighborhoods have taken matters into their own hands to protect themselves and become wise to fire.

An Opt-In Approach

A few years ago, Lon Leneve was sitting with a neighbor in his Awbrey Butte neighborhood looking around when it dawned on them just how vulnerable they were to fire.

"He and I were just observing the butte and realized how much fuel we had on the butte in terms of trees and shrubbery," Leneve said. This observation led Leneve to deeply research how the community could be more proactive in wildfire mitigation.

Leneve is part of the Awbrey Butte Owner's Association and neighborhood, a community of over 780 properties. He said that before 2021 the community was Firewise "light." Firewise USA is a national program that helps neighbors organize and take action to protect their homes and reduce their community's wildfire risk. It is primarily an education and resource tool rather than a set of strict guidelines. Nationally, Oregon has the second-highest number of Firewise sites (eight homes is the minimum requirement for a site) behind California, with 282 sites. Sixty-seven of those are in Deschutes County, making it the fifth-highest per county in the nation. The only county in the state with more sites is Jackson County, according to Christie Shaw, Oregon Department of Forestry's national fire plan coordinator and the state's Firewise liaison.

Among the low-hanging fruit recommendations from Firewise: Ensure there are no combustible materials within 5 feet of a home, clear gutters, install 1/8-inch metal mesh screening on vents and repaire or replace missing roof shingles. Maintaining defensible space is key to a home's ability to survive a fire.

A post-fire study of homes in San Diego County, California affected by the 2007 Witch Creek Fire found that 67% of homes with unmaintained vegetation were destroyed. That number dropped to 32% for homes with maintained defensible spaces. However, like with Leneve's observation of Awbrey Butte in 2020, many areas around Deschutes County are overgrown and unmaintained.

"We need to change the culture here," said Melissa Steele, a Bend Fire and Rescue inspector. "If you move to the Pacific Northwest, you have to do your defensible space. It is just one of those things. Changing that culture in the prevention world has been a little bit of a struggle," she added.

The struggle, Steele said, is in part because people feel that defensible space measures don't apply to properties inside Bend or near the city center. "What I like to tell people is that when I lived in Paradise [California, the site of the 2018 Camp Fire, the deadliest wildfire in California's history] the fire started seven miles away from my house," Steele said. "I lived in the middle of town and that fire started in the forest. But because of embers, because people didn't do defensible space and because of structure-to-structure ignition, it spread."

Steele works with homeowners and association groups like Leneve's to educate and advise on best practices for fire protection. There are monthly meetings, regular outreach activities, incentive programs that offer grants for qualifying properties and ongoing support for homeowners trying to harden their property to fire. All of it is on an opt-in basis.

Leneve, who is very involved with these efforts as well and serves as a mentor through Project Wildfire, would like to see elected officials take on more of a leadership role and enact policies with teeth.

"Communities like ours that are decades old are trying to reverse the trend of creating fuel and creating risk, and we're trying to reverse it as quickly as we can," Leneve said. "But what I would like to see is at the city level, like Bend, or Deschutes County, establish some form of code because we have no enforcement capability in our community and most don't."

Currently, neither the county nor city plan to implement their own wildfire-related codes. The movement and conversation related to local ordinances stalled out in 2020 when the state announced it would be tackling similar legislation. However, given the intense backlash from the first maps the state put out for SB 762, there is uncertainty about how this next version will be received. The new map does have some significant changes – it eliminated two hazard categories and now groups properties in low-, moderate- or high-hazard zones, in addition to reassessing pasture lands and irrigated croplands. Any new building codes would only apply to new construction or significant upgrades on existing homes, on properties designated as high-hazard that are at least partly in the wildland-urban interface. But concern remains.

"I'm anxious. I am quite anxious about these maps moving forward," said Phil Chang, Deschutes County Commissioner. "Whether there's going to be some classes of landowners who come forwards and just say, 'You can't do this to us.' Or are concerned about being regulated and making claims that this is going to cost them a lot of money."

Public comment period for the draft rules governing the map is now open and will run through August 15. The public will be able to comment on the draft map from July 18 until August 18 and a finalized map is expected to be published online on Oct. 1. Property owners in a high-hazard zone and within the WUI will be notified by letter and have until Oct. 15 to appeal the designation.