In a Land Birthed By Fire

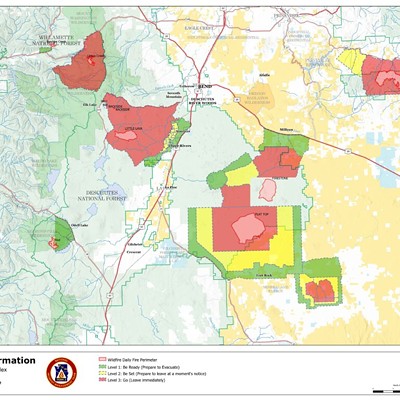

The final installment of our three-part series exploring how Central Oregon can safely live with fire.A lightning storm on July 22 lit up the sky over Ochoco National Forest about 5 miles north of Paulina, Oregon. The resulting strikes set off a fire that would eventually grow to nearly 87,000 acres, necessitate nearby evacuations and require the attention of hundreds of the nation's most skilled wildland firefighters and command teams. Exactly one month after the blaze was first reported, the fire was contained enough to be turned back to local control, and the people who helped fight it were dispatched to another inferno. Another makeshift campsite on a fire line. Another emergency requiring intense focus and energy.

Around the country there are 44 Complex Incident Command Teams, each with 50-90 workers, that are tasked with responding to the largest, most worrisome fires and coordinating the effort to combat them.

tweet this

This is the reality of fire season in the West. Each year we set new records. Fires are more frequent, more intense and burn through more acreage than in decades past. Fighting these complex blazes requires round-the-clock attention and monitoring from hundreds of specially trained and outfitted wildland firefighters, along with a strong logistics and leadership crew.

Around the country there are 44 Complex Incident Command Teams, each with 50-90 workers, that are tasked with responding to the largest, most worrisome fires and coordinating the effort to combat them. The people on the teams come from different backgrounds; many are employed with the U.S. Forest Service in some capacity. During fire season all must be ready to deploy within hours anywhere in the country. And they're all volunteers. This is the first year for these types of command teams. Before, there were two levels of teams to handle the more complex fires and largest disasters, but finding enough skilled volunteers to staff those teams was difficult, according to a Forest Service spokesman, so the agency decided to reorganize them into one type that can handle the most complex responses. But, in total there are fewer teams, meaning that when resources are stretched and fires are at their peak, requests for CIMTs may go unfilled.

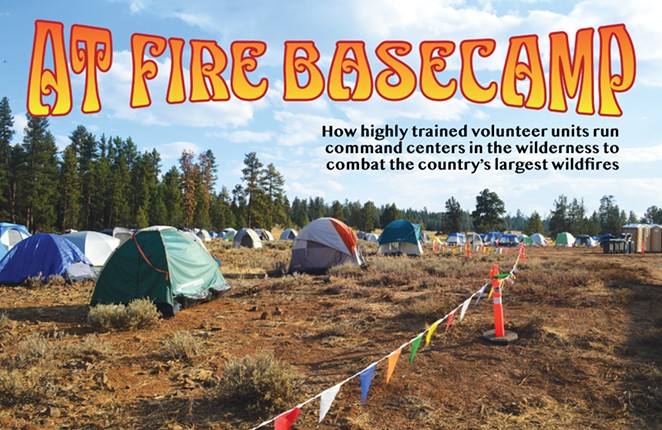

The Crazy Creek Fire, what the July 22 lightning start near Paulina would later be named, was in some ways a well-timed conflagration. Fire activity being what it is in Oregon during this record-breaking year, crews were nearby and ready to respond. A top-tier incident command team was available to be assigned to the fire. The team that came after them was also staffed up and ready for the mission. Within a matter of days, these teams can erect a self-contained fire base camp that functions like its own small city, in the middle of the wilderness. These basecamps are crucial to firefighters' safety, comfort and success — taking care of everything from food to laundry, to medical services and coordinating air and ground attacks on major conflagrations.

It's hard to overstate the threat that wildfires pose to the West. The Park Fire burning in California started two days after Crazy Creek and by press time has eaten through 429,603 acres, making it the fourth-largest wildfire in the state's history. To date it is 82% contained. In Oregon, over 1.5 million acres have burned statewide this year. The state total, just partway through fire season, surpasses the 10-year average of 1.2 million acres for Oregon and Washington combined. These trends aren't new.

"Drought and persistent heat set the stage for extraordinary wildfire seasons from 2020 to 2022 across many western states, with all three years far surpassing the average of 1.2 million acres burned since 2016," the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration states on its Wildfire Climate Connection webpage. "Extreme fire behavior during this period shocked many wildfire managers, as several huge blazes burned for months, others incinerated entire communities, and still others erupted during nighttime wind events, when firefighters could normally count on working the fire line."

And as this threat grows in scale and complexity, so too does the challenge of employing a workforce capable of meeting the task.

At Camp

A few weeks into the Crazy Creek Fire, I visited base camp to meet with incident command leaders and get a feel for the camps where thousands of firefighters around the country spend their summers jumping from fire to fire in two-week intervals.

The camp was 5 miles from one edge of the fire, in an area so remote that the Oregon Star Party hosts its week-long stargazing expedition there. The drive from Prineville, the nearest city, is about an hour. If it weren't for these camps, I'm told the hundreds of firefighters and support personnel assigned to the fire would have to stay in Prineville and commute to the fire line each day, or spend weeks at far-flung campsites where they'd have to pack their belongings in and out.

“The beauty of this is we can hit the ground and just take off.” —Doug Winn

Instead, firefighters set up tents in the grass and clearings around the outside of the main camp area. Most are in small, single-person tents. Some sleep in their cars. The real benefit of the base camp is in the logistics area. Entering the main artery of camp, large beige yurts are spread out every few yards in makeshift corridors. Next to each, a portable Starlink kit ensures that the operation teams within can communicate effectively with the outside world, sending daily reports and receiving critical weather and potential fire behavior information. Inside the yurts it's surprisingly clean and comfortable, thanks to large air conditioning units, overhead lighting and durable flooring. Desks are arranged throughout with computers and monitors. The walls are covered with large, full-color printouts of the fire. These large-scale maps are printed daily in a big blue school bus converted into a mobile print shop, which also handles hundreds of pages of documents daily for morning and evening briefings.

On this day, the wind is blowing smoke away from basecamp and the air is clear. It's still a few hours before dinner, so camp is relatively quiet as firefighters are out on the line. In the operations tent I meet Doug Winn, the logistics section chief for the California 1 CIMT. His job is to support firefighting efforts by supplying everything from food and water to showers and work clothes. No detail is too small. On any day his crew may be driving out thousands of feet of hose to firefighters on the front lines, coordinating packed lunches for hundreds and getting services and food out to workers at spike camps – smaller scale camps set up along the fire's perimeter that are too far from the main camp for daily commuting.

"I have a food unit leader, I have a facilities unit leader, I have a medical leader, a communications leader, a supply leader, a ground support leader — all of those positions, and then they have people who work under them," Winn says. When the team is deployed, they all go together throughout the year. "The beauty of this is we can hit the ground and just take off."

That level of coordination also allows them to seamlessly hand over operations to the next incident command team or to pack up and clear out quickly if needed, as Winn had to do when the wind shifted at a fire one year, cloaking camp in thick smoke for days on end. In the last decade, the impact of smoke exposure to wildland firefighters is drawing more focus with recent studies finding that there are short-term impacts (decreased lung capacity) and long-term ones, like an elevated risk of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease.

On the other side of the camp from Winn's yurt is a mobile unit that looks like an extra-long travel trailer equipped with trained medics and nurses to help assess injuries and provide care to anyone injured while at camp or on the fire line. Med Transport Inc., like every other company at the fire, is contracted through the Forest Service to assist. During the course of the fire, the team there acted as an urgent care — supplying oxygen to firefighters in need, provided over-the-counter medication to those in need and helping to stabilize a firefighter ahead of emergency helicopter transport to a nearby hospital.

“When we show up sometimes and all we do is fight fire the whole time and then we leave and the fire is still raging... yeah, that’s not so much fun.” —John Goss

In addition to caring for the people fighting the fire, incident command teams are in charge of caring for the land they're protecting. John Goss, the commander for California 1 CIMT, compares it to being in someone else's home.

"We do our very best to be good guests," he says. As commander, Goss works with the landowners the fire is impacting, in this case the Forest Service and U.S. Bureau of Land Management, to ensure that the team is doing what it can to protect natural and cultural resources. In some cases, this means spraying the bottom of vehicles before they go out into the forest to mitigate spread of noxious weeds or wrapping buildings or historic trees in protectant material to try to preserve them if the fire spreads. Checking in with those stakeholders happens frequently and requires care and consistency — at least for the 14 days he is in charge.

"Once we get here and we get that letter of expectations, we are delegated the responsibility of putting that fire out, and the cleanup that ensues after the fire is out," he said. But with these larger blazes, the work of putting the fire out could take much longer and require multiple teams to rotate through, a fact that is hard for Goss at times.

"It's always nice to finish something," Goss said. "When we show up sometimes and all we do is fight fire the whole time and then we leave and the fire is still raging...yeah, that's not so much fun."

End of the day

Just before 6 p.m. the men (84% of wildland firefighters identify as men, according to the U.S. Government of Accountability Office) trickle into camp, filling the showers and bathrooms before heading to a large pop-up tent festooned with twinkle lights and large flatscreen televisions. A food truck out front of the temporary dining hall serves giant plates of hot food: mashed potatoes, pinto beans, pulled pork, rolls and more. Experts estimate that wildland firefighters need around 5,000 calories to sustain themselves after a long day in the field. The average workday for a wildland firefighter on a fire is 14 hours.

One crew I spoke with during dinner was a three-person team out of Eager, Arizona. The men are part of Valkyrie Fire LLC, a small contract company run by Charles Reese. Reese is a longtime wildland firefighter who said he took a break from fighting fires last year to care for his father, but assembled a crew this year to get back out, in part because he missed it. Having worked at all levels of fires, he said this camp was like a hotel compared to others. There were times where he worked 16-hour days and ate military-grade MREs for every meal.

"Fire gets in your blood," he said. The adrenaline of working a fire combined with the camaraderie and brotherhood of camp draws him back. Addressing the youngest on his crew, Reese tells him not to get too used to the amenities at Crazy Creek. "You're getting spoiled," he says with a laugh.

Reese's three-man team is assigned to a larger team at the fire, led by an Australian firefighter who came over with four others from western Australia to help on Crazy Creek. They will be here for a month on fires. In addition to the international firefighters, there were three firefighters from the Virgin Islands and crews from a dozen states.

At its peak in mid-August, the fire had 721 people assigned to it. Within a week of my visit, the temporary camp city was packed up and California 1 CIMT members headed home for hopefully a couple of days of rest before their next assignment.

As of Aug. 26, there were 56 large active wildfires being managed nationally, and around 18,000 wildland firefighters and support personnel working to fully suppress them. Over 5.5 million acres have burned so far this year. In Oregon, it's already been a historic fire season for acreage burned and in the Pacific Northwest the fire season usually peaks in August – no doubt more of these temporary camp-cities will be popping up throughout the region in the weeks to come.

—This story is powered by the Lay It Out Foundation, the nonprofit with a mission of promoting deep reporting and investigative journalism in Central Oregon. Learn more and be part of this important work by visiting layitoutfoundation.org.

![Race for Deschutes County Sheriff Heats Up ▶ [With Video]](https://media2.bendsource.com/bend/imager/race-for-deschutes-county-sheriff-heats-up/u/r-bigsquare/21832439/news2-1-ab920340a63d5120.jpg?cb=1726161706)